Action research for promoting inclusive teaching

June 20, 2025 2025-06-20 16:26• CHAPTER 7 •

Action research for promoting inclusive teaching

Eleni Katsarou and Elia Fernández-Díaz

7.1 A critical approach to educational change

In this chapter, we will first argue for the use of educational action research in the current faculty training scenery in contemporary higher education. Secondly, we will justify the relevance of using this strategy by showing the opinions of faculty from different universities who have participated in staff development processes established within the framework of a European-wide project on inclusive teaching in higher education. The COALITION (2023) project aimed to foster professional development in higher education, promote critical teaching, and enhance reflection on praxis through action research processes. Finally, we will illustrate with guidelines and resources how educational action research can be used in university teaching.

We live in a globalised, technologically accelerated, changing world, with economic, social, health, and war crises. It is a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world (Stein, 2021). At this juncture, higher education must improve the way it faces the challenges of joining the knowledge-based economy, the information society, and global culture from a critical and emancipatory perspective.

However, the mercantilist and meritocratic tendencies established in the university context, in the so-called era of accountability, have prioritised training for employability of a utilitarian nature (Ball 2012, 2016; Sparkes, 2013) to the detriment of democratic, activist and collective training processes (Fernández-Díaz et al., 2018; Groundwater-Smith & Mockler, 2009). At the base of the strong regression, we are witnessing lie the strong neoliberal and neoconservative pressures that reach all educational sectors (Giroux, 2013; Rivas, 2020; Säfström & Månsson, 2021; Starr, 2021). Likewise, in this new scenario, new training paradigms are required to face a knowledge society characterised by accelerated growth, greater complexity and a tendency towards rapid obsolescence. These training paradigms seek to place the epicentre in the student, assigning the faculty member a new role as facilitator and overcoming the traditional form of transmission and accumulation of knowledge (Κatsarou & Tsafos, 2013; Moore & Gayle, 2010). At the same time, there is a demand for a new conception of academic training and a revaluation of the teaching function that encourages the motivation of university teaching staff and recognises efforts aimed at improving quality and educational innovation through the development of policies focused on lifelong learning in the field of university teaching (Imbernon, 2017).

In short, the intended transformations of the training paradigm inscrutably entail the need to rethink educational change and professional development from a critical and inclusive approach in order to respond to the diversity of the student body in face-to-face and virtual contexts, promoting the creation of communities of practice to investigate the necessary changes in the university curriculum (Bonafé, 2014).

7.2 Action research for transformative development

Faced with the design of short-term, externally devised training processes, we need to promote the creation of collaborative environments that seek to reflect on practice in order to achieve sustainability of the changes and ensure the professional development of the faculty involved (cf. Rumiantsev et al., 2024). The mere updating of conceptual and methodological references without experiential support does not guarantee changes in teaching practice, and it is necessary to implement contextualised, systematic and participatory processes that address the cyclical and non-linear nature between beliefs, practices and transformations, as well as to establish and consolidate collegiate learning

groups and communities where faculty learn to give and receive critical support (Curry, 2008; Putnam & Borko, 2000).

We will now explore the role of action research as a tool that enables the design of formative processes focused on collaborative inquiry and the transformation of practice based on the principles of equity, inclusion and quality (Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts, 2022b). That is, formative processes aimed at creating communities of practice that promote reflective and collaborative sharing of experiences among faculty in order to improve and systematise the design of learner-centred inclusive teaching practices (Netolicky, 2016; Rahman, 2023). Several studies show the relevance of action research in the sustainability of experiences that promote curricular transformation and faculty development (Gibbs et al., 2017). In this line, international contributions from different communities of practice that use action research approaches to implement training processes to promote critical and inclusive teaching stand out (Arvanitakis & Hornsby, 2016; McFadden & Smeaton, 2017).

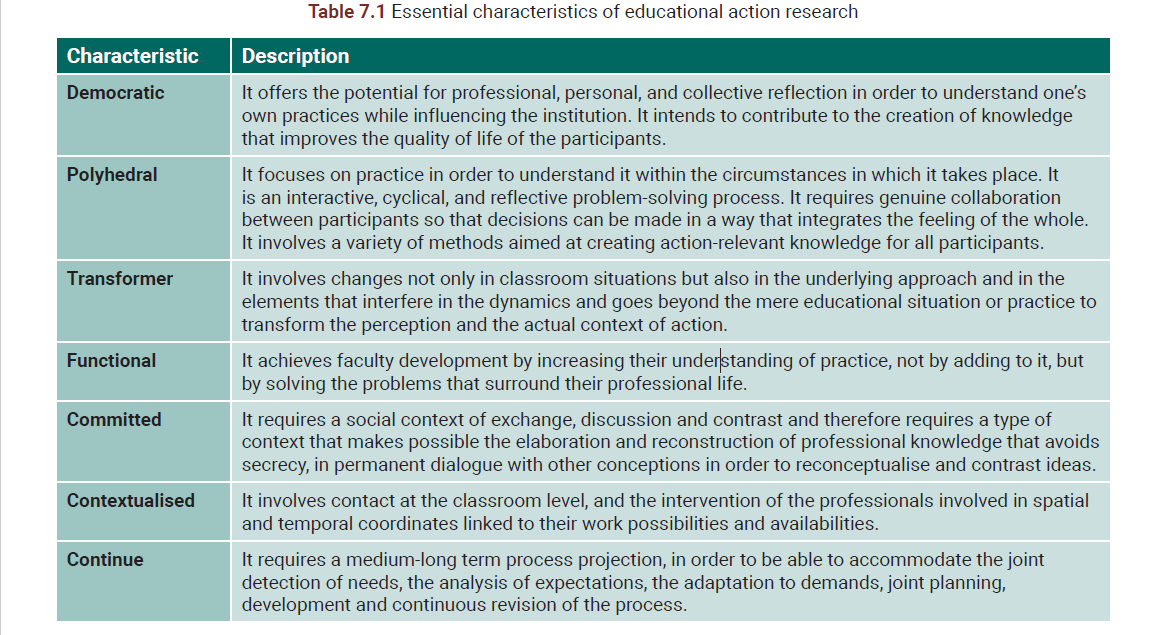

Underlying action research is a way of understanding teaching as a process of continuous search, and research, to introduce progressive improvements to teaching. Fundamental to this process is the reflective exploration of the teaching practice by the teaching staff themselves. Action research, therefore, is a means of optimising the teaching-learning processes that translates into an increase in professional development for teaching staff. As a methodology oriented towards educational and social change, action research can be characterised as a process that is built from and for practice, aiming to improve it through deliberate transformation, while at the same time seeking to understand it, demanding the participation of the subjects involved. From its origins, action research has been configured as a spiral of cycles of planning, action, observation, and reflection to implement a critical and systematic analysis of the situations under study and improvement. Today, because of the participatory convergence between different approaches, groups, and collectives, the incorporation of emerging emancipatory methodologies is proliferating (cf. Fernández-Díaz et al., in press). In this context, the spiral of cycles continues to be rethought as a juncture to favour the ecology of knowledge, proposing alternatives to linear, excluding, and hierarchical rationality. Action research encompasses a whole philosophy of life and is a process that requires commitment, an ethical stance, and persistence at all levels (Fernández-Díaz, 2024). Table 7.1 summarises some of its essential characteristics (Bausela, 2004; Rowell et al., 2015).

Global concerns, such as achieving inclusive, equitable, and quality education, can be implemented through action research. In this way, the contextual isolation that usually prevails in the usual short-term educational dynamics can be broken down and paths for sustained community improvement can be found, giving priority to horizontality and democratic decision-making. In other words, it paves the way for devising a reflection capable of questioning preconceived ideas and seeking proposals for improvement, improving the collaborative work culture and overcoming the meritocratic inertias that prevail in the current university context (Jayadinata et al., 2022; Jordan & Kapoor, 2016).

Global concerns, such as achieving inclusive, equitable, and quality education, can be implemented through action research. In this way, the contextual isolation that usually prevails in the usual short-term educational dynamics can be broken down and paths for sustained community improvement can be found, giving priority to horizontality and democratic decision-making. In other words, it paves the way for devising a reflection capable of questioning preconceived ideas and seeking proposals for improvement, improving the collaborative work culture and overcoming the meritocratic inertias that prevail in the current university context (Jayadinata et al., 2022; Jordan & Kapoor, 2016).

7.2.1 Action research and inclusive teaching: a valuable combination

Within the framework of the COALITION project, a staff development initiative has been implemented in various European universities through an action-research methodology in order to ensure that participating faculty members receive support and training from their peers to promote the development of inclusive practices in different contexts. Using different information-gathering instruments, such as interviews, reports, and task analysis, we have been able to obtain an overview of the main findings and difficulties encountered in the reflection on the inclusive practices implemented.

Through thematic analysis conducted in the above-mentioned material, we identified five main themes that were mentioned by the majority of the participants, each of which is composed of sub-themes. Here we present the themes and sub-themes we identified along with illustrative extracts from the material documenting our findings.

Theme 1: Impact on teaching practices

a. Use of Group Work: Collaborative assignments, group discussions, and peer feedback. Use of tools like online survey forms, quizzes, and shared documents for enhancing inclusivity and cooperation.

Students worked in diverse three-member groups to complete a project, allowing them to collaborate and leverage each other’s strengths.

b. Differentiated Instruction: Tailoring learning activities to diverse student needs, for example, providing multiple formats of learning materials.

I have ensured that these tools were accessible to everyone and provided materials in multiple formats.

c. Changes in Assessment Practices: Some faculty members planned to modify their assessment methods to better address students’ unique learning needs and preferences.

As a result of this action research, I would increase the use of formative assessments that are more personalised to student needs, offering a variety of ways for students to demonstrate their understanding, focus more on flexible groupings within the classroom to allow students with similar learning needs to collaborate while ensuring opportunities for mixed-ability interactions and incorporate more scaffolded feedback loops, where students receive timely, constructive feedback, allowing them to correct and learn from their mistakes throughout the course.

d. Shifts Toward Experiential Learning: Action research led some faculty members to incorporate more hands-on and experiential activities, such as role-playing and peer feedback, into their lessons.

Theme 2: Impact on faculty

a. Increased Awareness of Inclusion Issues: faculty reported that action research helped them recognize the challenges and exclusions that students face, particularly in relation to gender, socioeconomic status, and cognitive diversity.

Action research has helped me become aware of what inclusion is in practice and identify firsthand the problems and exclusions that students encountered through the tools I used.

As a result of this action research, I will implement more student-centred and collaborative learning activities to promote active engagement and participation among students.

b. Collaboration with Colleagues: Action research fostered collaboration among faculty, allowing them to share strategies, reflect on outcomes, and develop more inclusive practices together.

c. Openness and respect to students’ voices: Action research made faculty more open to their students’ voices.

Try to listen to your students, elaborate their views and respect them. Be humble and not authoritarian. Do not worry if you are losing control. We are humans, let’s do it together.

I learn every day from my students. I ask them to evaluate my way of teaching and suggest changes, so the lesson is not boring. They often talk about test questions and say that it is far away from their reality and ask me why I put this. I want to remember that my students are my teachers and we can construct the lesson together.

d. Reflection and Adaptation: Faculty emphasised the importance of continuous reflection and adaptation, identifying areas for improvement based on feedback and observations during the action research process.

By committing to continuous improvement through action research, I contribute to a dynamic, responsive, and effective educational environment.

I ask students to ask more questions or provide informal feedback so that I have time to redesign the lesson the next time. So I am always open to redesign.

This reflects a commitment to ongoing professional development and adaptability in teaching strategies.

e. Commitment to Continuous Improvement and to Continuing Action Research: Many faculty members expressed a strong likelihood of continuing to use action research in the future, recognizing its value in fostering continuous improvement in teaching and student outcomes.

I am highly likely to implement action research again because it provides real-time feedback and allows for continuous improvement. The iterative nature of action research makes it effective for understanding and adjusting teaching strategies to promote positive learning behaviours.

Theme 3: Impact on students

a. Improvement in Student Engagement and Participation: Faculty members noted increased student engagement and active participation when inclusive methods like group projects, case studies, and open dialogue were implemented.

Students who were previously disengaged became more active in class discussions. Higher levels of student engagement and participation in learning activities.

b. Development of Critical and Soft Skills: Inclusive teaching strategies led to better engagement and the development of both academic and social skills, reinforcing the importance of creating equitable learning environments.

Reports mentioned that students developed collaboration, communication, empathy, and critical thinking skills.

Students developed critical and soft skills such as collaboration, communication, empathy, and critical thinking.

The extent to which it improved behaviour was noticeable in how students interacted with the material and each other, showing increased motivation and self-regulation.

c. Change in Class Dynamics – Sense of Belonging and Support: Several reports highlighted that inclusive teaching created a more supportive and respectful environment where students felt valued and part of the learning community.

Additionally, they [the students] reported a stronger sense of belonging and feeling valued in the classroom.

Students who were previously disengaged or hesitant to participate became more active in class discussions and activities. They reported a stronger sense of belonging and feeling valued in the classroom.

Theme 4: Difficulties and challenges faced

a. Time Constraints: Limited teaching time was frequently cited as a challenge that restricted the full implementation of inclusive tools and action research. This reflects a fundamental constraint faced by faculty, where ambitious inclusive teaching strategies clash with the practical realities of tight course schedules.

Firstly, the limited teaching time does not give much room to make extensive use of the inclusion tools. The nature of the course.

Also, since inclusive practices can be time-consuming, I had to make extra planning and preparation. Moreover, I had to ensure effective collaboration and communication among all students.

b. Difficulties in Balancing Diverse ways of Learning: Faculty found it difficult to cater to different cognitive levels, socioeconomic backgrounds, and learning preferences within a single course.

Ensuring equity while addressing diverse cognitive and emotional needs required careful planning.

The most difficult part of designing this action research with inclusion as the first priority was balancing the diverse needs of all students while maintaining academic rigor. Ensuring that the differentiated strategies catered to a wide range of abilities, backgrounds, and learning styles required thoughtful planning.

c. Technological Barriers: Some faculty members faced technical difficulties, such as poor signal quality, that hindered the successful integration of online tools and apps in teaching, indicating the resistance faculty might encounter, not just from time and other practical constraints, but also from the attitudes and engagement levels of students.

d. Resistances From Faculty and Students

To exclude other factors that would hinder the evaluation of action research in terms of inclusion such as indifference, lack of motivation [from students] as well as to integrate this action into modern medicinal chemistry.

Theme 5: Training needs identified

Need for Institutional Support: Faculty expressed concerns about the lack of pedagogical training and incentives for inclusive practices in higher education. Group work and peer feedback were essential in fostering inclusion, but these activities need careful facilitation to ensure participation from all students, especially those less confident or introverted. Especially, faculty members in science disciplines noted that they lacked formal training in inclusive teaching and pedagogy, which made it challenging to implement action research effectively. Faculty mentioned that university systems prioritize publications over teaching quality, leaving little motivation or support for conducting action research to improve teaching practices.

Like most faculty members in the sciences, I have not been trained in teaching. Usually, teaching is done through personal experiences, right or wrong, without considering many contemporary issues that pedagogy addresses.

7.3 From theory to action

The project has made it possible to generate a European-wide community of practice to promote formative scaffolding among faculty for the achievement of inclusive teaching through action research. For this purpose, different training tools and processes have been developed and used. For example, the COALITION Workshop on Action Research (https://goo.su/eH0O) explains the basic characteristics of a methodology that supports teaching and reflecting at the same time. Both theoretical approach and experiences developed in the university context are provided in this workshop. The workshop shows some examples of improving teaching and curriculum through action research and others that highlight how action research can support faculty development.

This training resource also answers questions related to educational action research and its use in higher education, such as what faculty, support staff, and students gain from the action research procedures or the difficulties that they may face. Finally, it focuses on the reflective nature of action research and proposes some means for fostering reflection in the community of practice formed to conduct each action research.

We have illustrated how action research in higher education is used as a means of developing faculty members’ capability to teach and facilitate learning as it entails the enhancement of pedagogical practice through reflection and participatory research into practice (Gibbs, Angelides, & Michaelides, 2004). After a theoretical review of the need to claim the use of action research as a strategy to promote the transformation of university teaching practice in order to achieve inclusive teaching and promote professional development taking into account the current university context, we showed the findings by landing squarely on the analysis of the experiences under the training process. Finally, relevant materials and resources have been provided, sharing the formative experiences developed under the COALITION project.

7.4 References

Arvanitakis, J., & Hornsby, D. (2016). Universities, the citizen scholar and the future of higher education. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ball, S. J. (2012). Performativity, commodification and commitment: An I-spy guide to the neoliberal university. British Journal of Educational Studies, 60(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.650940

Ball, S. J. (2016). Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Futures in Education, 14(8), 1046-1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316664259

Bausela, E. (2004). La docencia a través de la investigación-acción. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 35(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie3512871

Bonafé, J. (2014). Pedagogía de la desobediencia. Foro de Educación, 12(17), 17-19. https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.2014.012.017.001

COALITION (2023). Needs analysis of the faculty members concerning inclusive student-centred pedagogies. study report. Bucharest: Romania.

Curry, M. W. (2008). Critical friends’ groups: The possibilities and limitations embedded in teacher professional communities aimed at instructional improvement and school reform. Teachers College Record, 110(4), 733-774. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811000401

Fernández-Díaz, E. (2024). Hacia una universidad comprometida con la democratización del conocimiento: surcando espacios para la siembra colectiva desde una convergencia participativa sentipensante. In J. A. Hernanz Moral, Educacion a lo largo de la vida para el diálogo y la transformación social (pp.197-221). Barcelona: Octaedro. http://doi.org/10.36006/09594-1

Fernández-Díaz, E., Rodriguez-Hoyos, C., & Calvo-Salvador, A. (in press). Promoting participation through visual narrative inquiry to recreate teacher learning-practice. Professional Development in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2023.2193196

Fernández-Díaz, E., Rodríguez-Hoyos, C., Calvo Salvador, A., Braga Blanco, G., Fernández-Olaskoaga, L., & Gutiérrez-Esteban, P. (2018). Promoting a participatory convergence in a Spanish context: an inter-university action research project using visual narrative. Educational Action Research, 27(3), 362–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1546607

Gibbs, P., Angelides, P., & Michaelides, P. (2004). Preliminary thoughts on a praxis of higher education teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 9(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251042000195367

Gibbs, P., Cartney, P., Wilkinson, K., Parkinson, J., Cunningham, S., James-Reynolds, C., Zoubir, T., Brown, V., Barter, P., Sumner, P., MacDonald, A., Dayananda, A., & Pitt A., (2017). Literature review on the use of action research in higher education. Educational Action Research, 25(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1124046

Giroux, H. A. (2013). Neoliberalism’s war against teachers in dark times. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies, 13(6), 458-468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708613503769

Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2009). Teacher professional learning in an age of compliance: mind the gap. Springer.

Imbernon, F. (2017). Calidad de la enseñanza y formación docente. Barcelona: Octaedro.

Jayadinata, A. K., Hakam, K. A., Muhtar, T., Supriyadi, T., & Julia, J. (2022). ‘Publish or perish’: A transformation of professional value in creating literate academics in the 21st century. International Journal of Learning, Teaching & Educational Research, 21(6), 138–159. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.6.9

Jordan, S., & Kapoor, D. (2016). Re-politicizing participatory action research: Unmasking neoliberalism and the illusions of participation. Educational Action Research, 24(1), 134–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1105145

Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts, K. (2022b). The ‘naked’ syllabus as a model of faculty development: Is this the missing link in higher education? International Journal for Academic Development, 28, 451-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2022.2025814

Katsarou, E., & Tsafos, V. (2013). Student-teachers as researchers: towards a professional development orientation in teacher education. Possibilities and limitations in the Greek university. Educational Action Research, 21(4), 532-548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2013.851611

McFadden, A., & Smeaton, K. (2017). Amplifying student learning through volunteering. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 14(3), 6.

Moore, T., & Gayle, B. (2010). Student Learning Through Co-curricular Dedication: Viterbo University Boosts faculty/

student research and community services. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, 4, 1-7.

Netolicky, D. (2016). Rethinking professional learning for teachers and school leaders. Journal of Professional Capital & Community, 1(4), 270-285. www.emeraldinsight.com/2056-9548.htm

Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029001004

Rahman, M. H. A. (2023). Faculty development programs (FDP) in developing professional efficacy: A comparative study among participants and non-participants of FDP in Bangladesh. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100499

Rivas, I. (2020). Educational research today: from the forensic role to social transformation. Márgenes, 1(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v1i1.7413

Rowell, L. L., Yu, E., Riel, M., & Bruewer, A. (2015). Action researchers’ perspectives about distinguishing characteristics of action research: A Delphi and learning circles mixed-methods study. Educational Action Research, 23(2), 243-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2014.990987

Rumiantsev, T. W., van der Rijst, R. M., Kuiper, W., Verhaar, A., & Admiraal, W. F. (2024). Teacher professional development and educational innovation through action research in conservatoire education in the Netherlands. British Journal of Music Education, 41, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051723000414

Säfström C. A., & Månsson, N. (2021). The marketisation of education and the democratic deficit. European Educational Research Journal, 20(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211011293

Sparkes, A. (2013). Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health in the era of neoliberalism, audit and New Public Management: Understanding the conditions for the (im)possibilities of a new paradigm dialogue. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 5(3):440-459. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.796493

Starr, K. (2021). Neoliberalism, education policy, and leadership observations. The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39666-4_98-1

Stein, S. (2021). Reimagining global citizenship education for a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world. Globalisation, Societies & Education, 19(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1904212