Peer observation as a reflective tool to build inclusive curricula

June 20, 2025 2025-06-20 15:02• CHAPTER 5 •

Peer observation as a reflective tool to build inclusive curricula

Kallia Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts

5.1 Reflective collaborative practice

Peer observation, when approached as a collaborative and developmental practice rather than an evaluative exercise, offers a unique opportunity to enhance reflective teaching and support the design of inclusive curricula (MacKinnon, 2001; Peel, 2005; Tobiason, 2023). Rather than being used solely for performance appraisal or compliance, peer observation can serve as a catalyst for pedagogical insight and curricular transformation. Within the framework of Inclusive Student-Centred Pedagogies (Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts, 2023), and grounded in the broader social model of inclusion (Hockings, 2010), this chapter explores how peer observation facilitates critical reflection on teaching practices, enabling educators to interrogate assumptions, adapt instruction, and co-design curricula that are responsive to diverse learner needs. By repositioning peer observation as a reflective and reciprocal process, we highlight its potential to cultivate inclusive learning environments and support faculty in aligning curriculum content, engagement strategies, and assessment with inclusive values.

In higher education, where teaching methods must continuously adapt to meet diverse student needs, peer observation offers faculty a unique opportunity to reflect on their practices, gain new insights, and refine their teaching strategies. When approached with a reflective mindset, using structured rubrics, and engaging in meaningful post-observation discussions, peer observation can significantly enhance teaching practices. This chapter guides how faculty can effectively use peer observation as a tool for self-development, with a particular focus on inclusive teaching practices. It aims to transform the perception of peer observation from a punitive assessment tool to a means of introspection and community building (O’Keeffe et al., 2021).

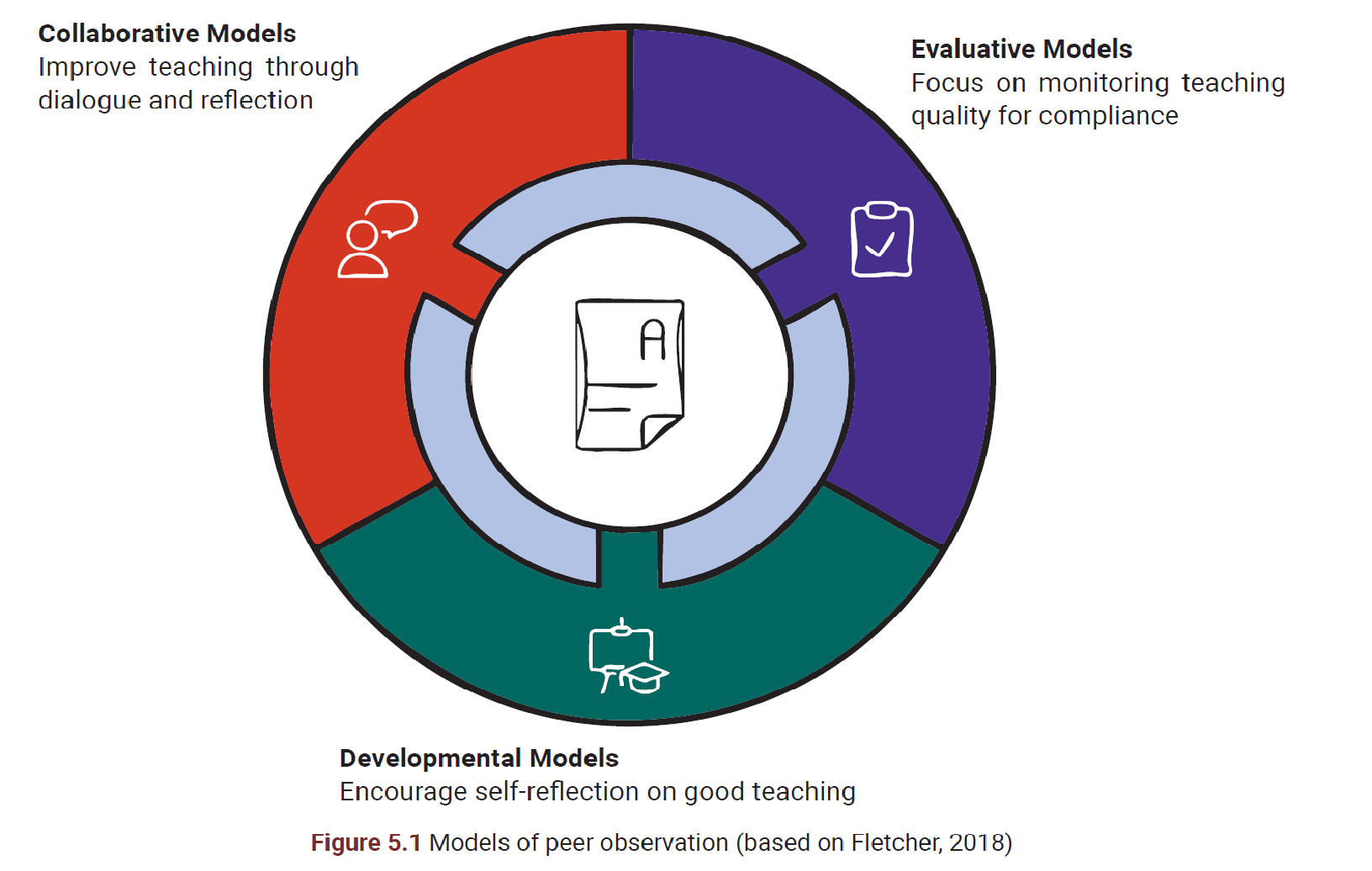

Fletcher (2018) summarised the literature on peer observation of teaching into evaluative models, developmental models, and collaborative models of peer observation (see Figure 5.1). Where evaluative models of peer observation focus merely on monitoring teaching quality to ensure compliance with the standards, developmental models aim to encourage faculty self-reflection on what constitutes good teaching (cf. Yiend, Weller, & Kinchin, 2012). The collaborative models intend to improve teaching through dialogue and mutual reflection. However, as Brookfield (1995) noted, peer observation often reproduces existing power dynamics within academic institutions. In evaluative and developmental models, power imbalances can lead to detrimental, unfair, and unsustainable outcomes unless critical reflection is at the core of the process. Even in collaborative models, tensions may arise if both parties feel entitled to offer unsolicited advice or promote agendas that the other is not prepared to embrace.

This chapter discusses the benefits and challenges of using peer observation as a reflective tool for self-development, particularly from the observer’s perspective. Emphasis is placed on the critical reflection practices that enable faculty to continually reassess and realign their own inclusive teaching practices. As Darling-Hammond (2000) emphasised: ‘helping faculty develop the capacity to inquire systematically and sensitively into the nature of learning and the effect of teaching is a central goal of academic development’.

5.2 Collegial dialogue and sense of community

Examining what constitutes ‘good teaching’ has been a focal point of global research in higher education (Kember & Kwan, 2000; Ottenhoff-de Jonge et al., 2021; Samuelowicz & Bain, 2001). The challenges faced by academics, such as navigating increasing diversity in disciplines, meeting growing student expectations, responding to new demands in inclusive course design and delivery, and adhering to the rising emphasis on professional qualifications, render a clear definition of good teaching as complex and multifaceted. Researchers have long recognised the value of reflexive peer observation schemes for academic development, which vary in scope and approach. Donnelly (2007) highlighted the importance of purposeful critical reflection on classroom practice and the challenging of assumptions through shared reflective dialogues with colleagues. Such practices encourage active self-development, with participants focusing on reflecting upon their own teaching rather than assessing or judging others’ practices.

5.2.1. Obeservee’s learning by focusing reflective practice

Self-reflection and peer observation are not new concepts. Their theoretical foundations are rooted in experiential

learning cycles, such as those described by Dewey (1933) or Kolb (1983), and Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy, if observation involves critical self-reflection rather than a mechanical process. Reflecting on practice is considered conducive to enhancing faculty’s self-efficacy (Korthagen, 2004). Osterman and Kottkamp (1993) emphasise the developmental potential of peer observation, noting that ‘reflection is viewed as a means by which participants can develop greater self-awareness about the nature and impact of their performance, an awareness that creates opportunities for professional growth and development.’ However, the pressure on the faculty member being observed can make this practice stressful and counterproductive, despite good collegial intentions.

Peer observation is often conducted within a formal review process mandated by institutions, designed for quality evaluation, teaching improvement, and the dissemination of best practices. Depending on the specific objectives, this process may involve administrators, senior faculty members, or colleagues, leading to various power dynamics between the observer and the observed. It is crucial to understand how these dynamics can affect learning outcomes. Traditionally, the learning opportunities provided by peer observation have been analysed from the perspective of the observed faculty member. However, there is growing recognition of the significant benefits that peer observation can offer to the observer. Bell and Mladenovic (2008; 2015) found that changes in teaching often result from a reflective process, with many tutors in their study citing the benefits of observing the teaching of another faculty member over receiving feedback.

According to Brookfield (1995) and Amundsen & Wilson (2012), the focus on reflective practice rather than outcomes equips faculty members with a process they can use throughout their academic careers, adaptable to various contexts, including solitary reflection after teaching or collaborative reflection with colleagues and students on curriculum design. Non-evaluative peer observations, conducted across the campus or within departments, can diminish the stigma of evaluative observation by fostering collegial dialogue and strengthening a sense of community.

5.2.2 Observer’s learning through a student’s perspective

The substantial learning advantages for the observer are increasingly acknowledged by scholars such as Hendry and Oliver (2012), who draw on social cognitive theory, and Tenenberg (2016), whose interpretive-phenomenological analysis suggests that peer observation reduces the ‘cost’ in terms of time and effort for both parties. Marin and Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts (2024), assert that participants who are willing to reflect on their teaching seem keen on learning new teaching strategies, affirming their current practices, recognizing challenges, and benefiting from feedback received during peer observation.

Another key advantage of this approach is that it allows observers to view a lecture or seminar from a student’s perspective, stepping away from concerns about content and class management. This shift in perspective enables observers to focus on how students engage with delivery modes, resources, materials, and learning activities. Hendry and colleagues (2021) emphasized that a significant part of the peer observation experience involves watching students’ reactions to their colleague’s teaching and noting their level of engagement.

5.3 Practical issues & samples

In this section, we examine the Greek context to illustrate how collaboration among university authorities, policymakers, and academic developers within the University Centres for Teaching and Learning can disrupt a non-reflective and non-inclusive academic culture. We highlight how these efforts culminated in the European project COALITION (2023) and explore how faculty at our universities perceived the use and efficacy of peer observation of teaching as a reflective tool. Additionally, we share reflections from faculty in Greece and Latvia who participated in this peer observation project.

5.3.1 Disrupting academic culture: the Greek experience

Transforming existing academic culture requires time and sustained effort. In the Greek Higher Education context, peer observation was first introduced in 2019 at the University of Crete under the name ‘Open Amphitheatre.’ Initially,

this initiative aimed to counterbalance potential faculty resistance to student-centred teaching and learning policies, as well as to mitigate top-down pressures for compliance. The intervention was bottom-up, initiated as part of the teacher training initiative, which primarily sought to facilitate the exchange of teaching practices.

Two faculty members from each department participated, with the freedom to choose whom they would observe across campus, ensuring their anonymity throughout the process. It was made clear that peer observations were intended to improve the observer’s own teaching practices. Faculty members were provided with a peer observation protocol to guide their observations and subsequent reflections on their own practices. A typical follow-up involved organising a roundtable discussion to disseminate the impact of peer observations and address four key questions:

• What were the key takeaways from participating in “Open Amphitheatre”?

• How did it contribute to the improvement of your teaching practice?

• What changes are you planning to make to your module as a result?

• What changes do you recommend for faculty development at our university?

This practice is ongoing, and the positive feedback received from participants has inspired the integration of peer observation into the faculty development processes in other universities.

5.3.2 Qualitative data from faculty during the European project

Reflective reports provided by COALITION faculty participants reveal several key themes regarding the use of peer observation as a tool for academic development. A recurring theme is the effectiveness and structure of observation protocols, which were highlighted by nearly all participants. Action-oriented reflection on teaching practices, with an emphasis on inclusivity, was widely recognized as a key benefit of the peer observation process. Collaboration, adaptability, and the need for continuous professional development were frequently noted as essential components for improving teaching practices. Table 5.2 below summarizes the identified themes and their prevalence across participant responses.

Table 5.1 Summary of identified themes and their prevalence across participant responses

Peer observation extends beyond mere critique; it serves as a reflective exercise that enables educators to view their teaching practices through the lens of another observer. For example, one participant emphasized the significance of this reflective aspect, stating, ‘It provides an opportunity to reflect on one’s own practices from a different observational perspective’ (GR1). This reflective process can lead to substantial changes in teaching approaches, particularly in enhancing inclusivity.

5.3.3 Structuring peer observations for maximum impact

A well-structured peer observation process is crucial to its success. Participants in the project underscored the importance of having a clear, concise, and comprehensive observation rubric that may also serve modelling purposes. One participant noted, ‘The specific observation rubric was beneficial… it effectively encompasses all essential skills required for delivering an inclusive lesson’ (GR3). Another emphasized the value of combining ‘descriptive and numerical feedback,’ which facilitates a balanced evaluation that is both qualitative and quantitative (GR3). Using a structured observation rubric that includes both qualitative and quantitative measures ensures a thorough assessment of all aspects of teaching, particularly those related to inclusivity.

5.3.4 Fostering inclusive teaching through peer observation

Inclusive teaching is a cornerstone of modern education, and peer observation can significantly enhance these practices. Many participants observed that peer observation provided insights into how their colleagues addressed inclusivity in the classroom. For instance, one participant reflected, ‘Making real-time adjustments to the lesson was crucial… ensuring that everyone could actively participate’ (GR3). Another participant highlighted the importance of ‘good communication with students, genuine interest in their development, and creating a pleasant atmosphere’ as essential components of inclusivity (GR4). Peer observation can help identify and implement strategies that promote inclusivity, such as making real-time adjustments during lessons, fostering open communication with students, and creating a supportive classroom environment.

5.3.5 Engaging in reflective discussions post-observation

Post-observation discussions are a critical component of the peer observation process. These discussions provide a platform for faculty to exchange ideas, clarify observations, and discuss potential changes in teaching practices. One participant emphasized the value of these conversations, noting, ‘I engaged in a discussion with the colleague I observed regarding inclusivity issues… underscoring the importance of recognizing individual student challenges’ (GR3). Scheduling post-observation discussions to reflect on observed practices and share insights with colleagues offers excellent opportunities for professional growth. These conversations should focus on constructive feedback and practical strategies for enhancing teaching, especially in addressing the diverse needs of students.

5.3.6 Implementing changes based on observations

The ultimate goal of peer observation is to improve how teachers design learning environments. Many participants reported making changes to their teaching as a direct result of observing their peers. For example, one faculty member decided to ‘incorporate inclusive tools and teaching methods to sustain the pace and engagement of the class,’ such as using ‘multiple-choice questions and polls’ (GR1). Another participant planned to ‘promote a classroom environment where students feel free to express themselves without the fear of judgment’ (GR2). Actively implementing changes in teaching practices based on insights gained from peer observations can positively impact both faculty and student attitudes toward teaching and learning. Involving students in providing feedback on strategies that enhance engagement, participation, and inclusivity can also yield significant benefits.

5.3.7 Continuous professional development through peer observation

Peer observation should be viewed as an ongoing component of professional development, rather than a one-time

event. Participants in the project stressed the importance of integrating peer observation into regular teaching practice and came up with an action plan triggered by their observations. One participant expressed a desire for more frequent peer observations and involving students to receive more frequent feedback, stating, ‘We need peer observation, self-analysis, and more frequent feedback from students’ (LV1). By and large, the COALITION experience with peer observation demonstrates that, when structured and implemented thoughtfully, it can be a powerful tool for fostering reflective teaching practices, promoting inclusivity, and supporting continuous professional development.

5.4 Resources: illustrative materials

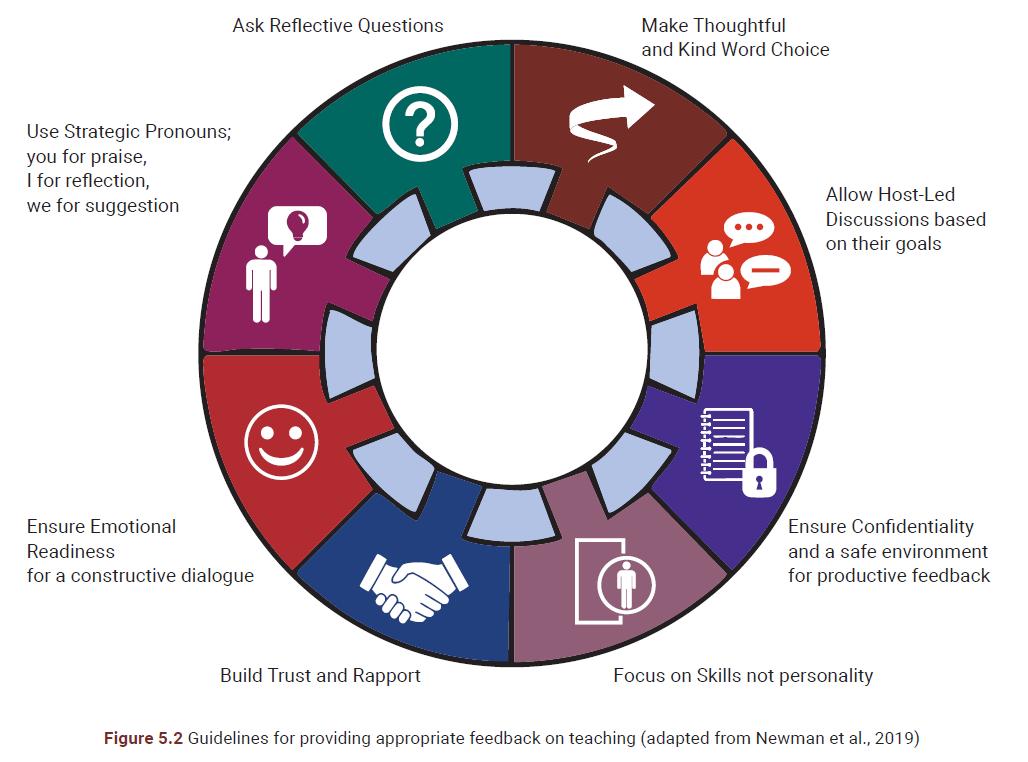

Several valuable resources support the development of reflective peer observation protocols. Since peer observation is frequently accompanied by follow-up discussions and peer coaching, novice faculty members are encouraged to consult the paper by Newman and colleagues (2019) for insightful guidance on providing effective peer feedback. Figure 5.1 summarizes the key takeaways from their work. If we had to choose the most important tip from this paper, it would be ‘check assumptions’ before thinking, asking, saying or doing anything that may jeopardize the outcome of peer observation.

Ask Reflective QuestionsMake Thoughtful and Kind Word ChoiceFocus on Skills not personalityAllow Host-Led Discussions based on their goalsUse Strategic Pronouns; you for praise, I for reflection, we for suggestionEnsure Confidentiality and a safe environment for productive feedbackBuild Trust and RapportEnsure Emotional Readiness for a constructive dialogue

5.5 Conclusion

In conclusion, peer observation as a reflective and dialogic process holds significant potential for advancing the development of inclusive curricula. When grounded in trust, reciprocity, and critical engagement, peer observation enables educators to examine their teaching practices, recognize diverse student needs, and collaboratively develop curricular approaches that prioritize inclusion and student agency. Rather than serving as a mechanism for judgment, peer observation becomes a formative space for mutual learning, fostering professional growth, pedagogical innovation, and sustained commitment to inclusive, student-centred curriculum development.

5.6 References

Amundsen, C. & Wilson, M. (2012). Are we asking the right questions? Review of Educational Research, 82(1), 90-126. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312438409 Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. London: Freeman & Co Ltd. Bell, A., & Mladenovic, R. (2008). The benefits of peer observation of teaching for tutor development. Higher Education, 55, 735-752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9093-1 Bell, A., & Mladenovic, R. (2015). Situated learning, reflective practice and conceptual expansion: effective peer observation for tutor development. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(1), 24-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.945163 Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. COALITION (2023). Needs analysis of the faculty members concerning inclusive student-centred pedagogies. study report. Bucharest, Romania. Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). How teacher education matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003002 Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. New York: Heath & Company. Donnelly, R. (2007). Perceived impact of peer observation of teaching in higher education. International Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, 19(2), 117-129. Fletcher, J. A. (2018). Peer observation of teaching: a practical tool in higher education. Journal of faculty development, 32(1), 51-64. Hendry, G. D., & Oliver, G. R. (2012). Seeing is believing: the benefits of peer observation. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 9(1), Article 7. http://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol9/iss1/7 Hendry, G. D., Georgiou, H., Lloyd, H., Tzioumis, V., Herkes, S., & Sharma, M. D. (2021). ‘It’s hard to grow when you’re stuck on your own’: enhancing teaching through a peer observation and review of teaching program. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(1), 54-68, https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1819816 Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: a synthesis of research. York: Higher Education Academy. Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts, K. (2023). Coaching instructors as learners: considerations for a proactively designed inclusive syllabus. Presentation at the Education Centre for Higher Education, Marijampoles Kolegija, Latvia. Kember, D., & Kwan, K. P. (2000). Lecturers’ approaches to teaching and their relationship to conceptions of good teaching. Instructional Science 28, 469-490. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026569608656 Kolb, D. A. (1983). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall. Korthagen, F. A. J. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching & Teacher Education, 20, 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.10.002 MacKinnon, M. M. (2001). Using observational feedback to promote academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440110033689 Marin, E., & Katsampoxaki-Hodgetts, K. (2024, March). University teachers’ willingness to support inclusive and effective student-centered learning. Presentation at the Future of Higher Education-Bologna Process Researchers’ Conference 5, Bucharest, Romania. https://fohe-bprc.forhe.ro/papers/ Newman, L. R., Roberts, D. H., & Frankl, S. E. (2019). Twelve tips for providing feedback to peers about their teaching. Medical Teacher, 41(10), 1118-1123. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2018.1521953 O’Keeffe, M., Crehan, M., Munro, M., Logan, A., Farrell, A. M., Clarke, E., Flood, M., Ward, M., Andreeva, T., van Egeraat, C., Heaney, F., Curran, D., & Clinton, E. (2021). Exploring the role of peer observation of teaching in facilitating cross-institutional professional conversations about teaching and learning. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 266-278, https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1954524 Ottenhoff-de Jonge, M. W., van der Hoeven, I., Gesundheit, N., van der Rijst, R. M., & Kramer, A. W. M. (2021). Medical educators’ beliefs about teaching, learning, and knowledge: development of a new framework. BMC Medical Education 21, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02587-x Peel, D. (2005). Peer observation as a transformatory tool? Teaching in Higher Education, 10(4), 489-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500239125 Samuelowicz K., & Bain, J.D. (2001). Revisiting academics’ beliefs about teaching and learning. Higher Education, 41(3), 299-325. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004130031247 Tenenberg, J. (2016). Learning through observing peers in practice. Studies in Higher Education, 41(4), 756-773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.950954 Tobiason, G. (2023). From content-centered logic to student-centered logic: can peer observation shift how faculty think about their teaching? International Journal for Academic Development, 28(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.2015691 Yiend, J., Weller, S., & Kinchin, I. (2012). Peer observation of teaching: The interaction between peer review and developmental models of practice. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.726967